Report

From Baghdad

By John Grant

After

24 hours in the air or loitering in airports, we were in our tenth hour of a

12-hour overland drive from Amman, Jordan, to Baghdad.

We were in two white Chevy Suburbans racing through the barren deserts of

western Iraq on a six-lane highway at times over 100 mph.

Forty

miles from Baghdad near Falluga we were stopped by a patrol of US humvees and a

tank parked in the middle of the highway. There

were a dozen Iraqi cars already stopped. Some

of us got out of the SUVs with

cameras ready. This brought a hail

of hollering from some very incredulous US soldiers walking toward us with M16s.

“Who

are you?” they wanted to know.

“We’re

a peace group,” we told them. “And we want to help bring you home.”

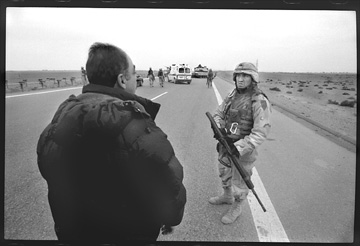

Fernando

started a conversation in homebody Spanish with Luis Gutierrez, a Mexican from

Chicago. At first a bit stunned, he

soon warmed to Fernando and was wishing us luck and to be careful.

Meanwhile,

the halted Iraqis were getting restless, which made the US soldiers even more

nervous. One of them told us the

now infamous Samarra ambush had happened the day before and things were tense.

As a second tank rolled in for reinforcement, a very prudent-minded first

lieutenant made the decision to let all the Iraqis pass and for us to pull over

– so he could clear us just who the hell these American civilians were.

It

was a quick lesson in the volatile mix that is the US occupation of Iraq.

Representing Veterans For Peace on the seven-day Global Exchange trip to

Iraq in December was both an honor and an eye-opener.

Three members of the group were parents with kids serving in Iraq and one

had had a son killed there in March. Parents

coming to look for their kids in a war zone was “legally unprecedented,”

according to a JAG full colonel we spoke with at occupation headquarters.

Fernando Suarez del Solar, whose son Jesus was accidentally killed by a

US cluster bomb, was the spiritual center of the group.

He was joined by Annabelle Valencia, who has a son and daughter in Iraq,

Michael Lopercio, who has a son, and Sean Dougherty, who has a daughter there.

The three VFP members – myself and Billy Kelly (Viet Nam vets) and

Michael McPhearson (a Gulf War I vet) rounded out the group.

It was a well thought out mix of people, thanks to Medea Benjamin, co

founder of Global Exchange and leader of the group.

Gael Murphy from Code Pink also made the trip and filmed everything.

When

we arrived at our hotel in Baghdad, we were met with a phalanx of German and

French TV crews on the sidewalk waiting. It

was our first sense that we were fairly high profile, thanks to Fernando and the

members from Military Families Speak Out.

Once the media circus was over, we took off for our first meeting, which

was in the area called Sadr City and was one of the more amazing events of the

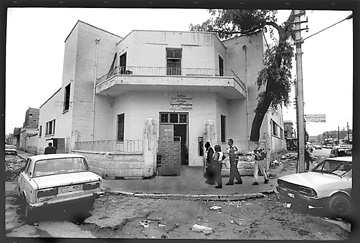

week. We arrived at a small mosque in this poor part of Baghdad.

Our meeting was with the father of a man shot dead by US soldiers.

I had read the story in the New York Times.

Muhanad Ghazi Al-Kabi, the leader of the Sadr City community council,

arrived one night at his office and was barred entrance by US soldiers.

An argument ensued, and a US soldier shot the man dead. The man’s father, Ghazi Al-Kabi, spoke to the group seated

on rugs on the floor directly across from Fernando. The dead man’s brother, Hani, spoke movingly in English.

The US military claimed the soldier’s action was provoked, that it was

a justified killing. The family

disdained that notion. Yes there

had been an argument, but he was in his own community and he was a community

leader going to his office in the Community Council, a body that operated under

the CPA-appointed Governing Council.

It was a very moving experience to witness the two fathers who had lost

sons exchanging views and handshakes. The

next day, we learned later, the US military visited the family and gave them

$10,000 and promised $3,000 a month for the killing.

They asked them to stop talking about the incident, something we were

told they refused. It seems our

little visit had had an impact.

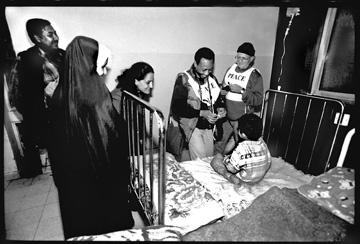

From there, it was a visit to a hospital where the doctors complained of having no antibiotics. One very angry doctor said a crew had come to paint the walls of the hospital, when what they really needed was medicines. We were taken to the Cardiac Care Unit and for maybe 15 patients there was one heart monitor.

It was the same story at an elementary school we visited the next day.

They had not seen the promised text books to replace the old Saddam books

and they reported a shortage of everything. But their walls had also been painted by a crew.

We

tried to find out the list of schools on the lucrative Bechtel contract but

could get no one to release that public information.

Our suspicion was that there was a slow trickle down of money and lots of

busy work at the end, and that our school was likely one of the one’s being

touted in the official story of reconstruction.

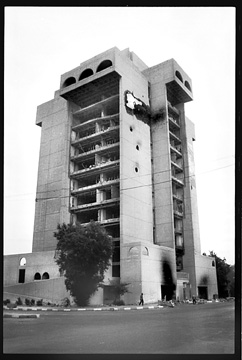

We found Baghdad to be a city of great pent-up energy and wreckage. After three decades of Saddam Hussein, 13 years of a US embargo and three wars ending in the US blitzkrieg invasion this Spring, profound infrastructure problems persist while US occupation leaders try to orchestrate their vision of a future for Iraq.

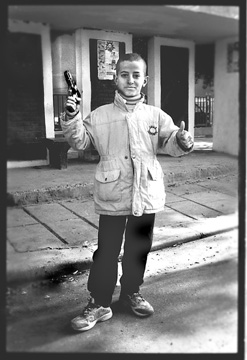

Five to seven hour gas lines have become a regular feature of Baghdad life. We spoke with people in one line and were told that a month after the Gulf War and throughout the embargo gasoline was plentiful and cost five cents a gallon.

“We live in a country floating on a sea of oil!” one man exclaimed. “Why do we have such lines?”

The fact resistance sabotage is cited as a cause doesn’t ease the exasperation or anger.

Electricity is sporadic and can go out for indefinite periods at any time, creating a vast market for small generators. Garbage mounts on the streets everywhere in the city. There is no phone system that any of us could see; Americans and Iraqis with means use cell phones with a Westchester, Connecticut area code. Sixty percent of the population is unemployed. In the city, unexplained gunfire is a normal occurrence. Women don’t feel safe on the streets.

While Saddam’s capture took over the news when we returned to the US, it was clear to us that none of the difficulties we saw were going to change any time soon. The Bush administration had opened a Pandora’s Box and the forces released were at play. And they were not going to be shoved back into a new box labeled MADE IN WASHINGTON anytime soon.

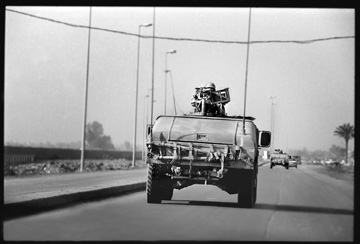

The US military occupation is evident everywhere.

Baghdad citizens are daily confronted with armed US patrols like the one we encountered on the highway. We saw them everywhere we went. Stand on any street corner for 45 minutes and you would see two humvees, a young soldier poked out the top of the first one pointing a machine gun forward and a soldier in the second one pointing a machine gun into the traffic to the rear.

These were our sons and daughters. In what the JAG colonel said was the unprecedented event, two group members drove to dangerous areas to actually see their kids. I accompanied Mike Lopercio to Falluga. We witnessed a half dozen mortar rounds fall short of the perimeter at one base we stayed at for a couple hours during the search. Annabel Valencia drove to Tikrit to see her daughter. Fernando Suarez de Solar trekked to the site in Diwaniya where his son was killed by a US cluster bomb. ABC News did a big story on that visit.

When I met a US soldier I told him or her we were “a peace group” interested in “bringing you home.” Every time the response was a smile, often an enthusiastic thumbs up.

My favorite encounter was with a lieutenant colonel outside at the CPA palace or “the green zone.” He was also a Viet Nam veteran, and once I gave him my opening rap, from his facial gestures and something he muttered about his wife at home it became clear to me he was pretty jaundiced about the whole situation. When I told him, “We want to bring you home now,” he laughed heartily and walked off. Later he ran into me inside the palace and slapped me on the back. “Good luck!” he said as we headed into our meeting with Major General John Gallinetti and Ambassador Richard Jones, Paul Bremer’s assistant. I felt he really meant it.

While US soldiers were our sons and daughters and our meetings warm, for Iraqis, contact with US soldiers is often very unpleasant. Their presence seems confusing to the ordinary Iraqis.

Wisal Alazawi, dean of the political science department of Nahrain University, summed up the dilemma of the military occupation.

“It’s absurd to talk about democracy while there is an occupation,” she told us. “The Governing Council is trying very hard, but the question is does the Council have the right to decide anything when everyone knows the US Occupation has veto power?” She was referring to the 24-member governing body appointed by Paul Bremer, head of the US Coalition Provisional Authority or CPA.

We were granted a meeting with Abdul Aziz al Hakim, the December president of the Governing Council. He is a Shiite leader, appointed by Bremer, who is interestingly out of step with the CPA plan for an Iraqi government, which would be selected by a caucus. Al Hakim and other Shiites would like a general election. He also said US occupation troops should leave. “When?” we asked. “How about tomorrow,” he answered.

A visit to the CPA headquarters in Saddam’s palace complex in the center of Baghdad makes it clear we are not planning to leave anytime soon. The CPA covers an area the size of Central Park with multiple rings of security, shuttle buses, cafeterias and trailer parks for all the Halliburton employees. Last week Bremer reportedly requested 1000 more employees. And, of course, the New York Times reports plans for a future embassy in Baghdad with 3000 employees, the largest in the world.

The question on my mind as I toured the CPA was who was this giant brain center plugged into: Baghdad or Washington? As a 19-year-old, I had witnessed MACV headquarters in Saigon, and this felt like deja-vu in Baghdad. As in Viet Nam, the CPA plan to orchestrate a government under military occupation seems more about control and disenfranchising selected sectors than it does about listening and real democracy.

Most Iraqis we spoke with were truly grateful Saddam was gone; but in the same breath they wanted the US military occupation to go. Shiites and Sunnis both told us the conflict among them and the Kurds was exaggerated and that they were fed up with war. Sunni Sheik Muayed Al-Addamy described these conflicts as “bubbles on the surface,” while Iraqi Nationalism was a stronger force deep in the water. The implication was that the US Occupation fueled that deeper Iraqi Nationalism.

What Iraq needs more than US bombs and young American soldiers in its streets is lots of monetary aid distributed by NGOs -- not by war profiteers like Halliburton and Bechtel. It needs inclusive and fair elections – not a government based on appointments by a US proconsul. And it needs a well-trained police and a temporary UN peace-keeping force – not under US military control.

No future in Iraq will be without rough spots – but the United States needs to ease its grip and allow the Iraqi talent, experience and energy we encountered to haul the nation up out of the ashes.

John Grant is president of the VFP chapter in Philadelphia.

Photos by John Grant

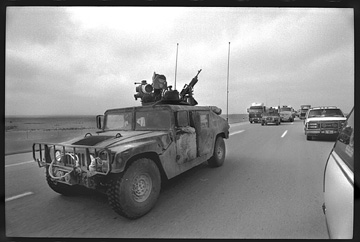

1) The group's Chevy Suburbans pass a US humvee leading a long oil convoy on the highway from Amman, Jordan, west toward Baghdad

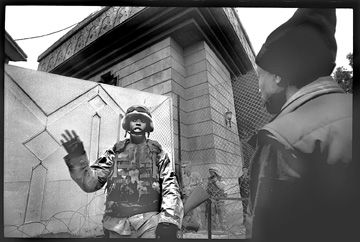

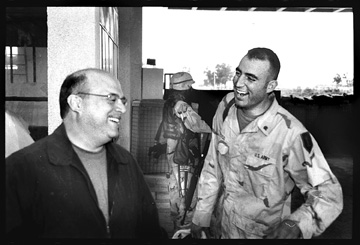

2) Fernando Suarez del Solar speaks Spanish to an incredulous Luis Gutierrez from Chicago at a roadblock on the highway near Falluga, west of Baghdad.

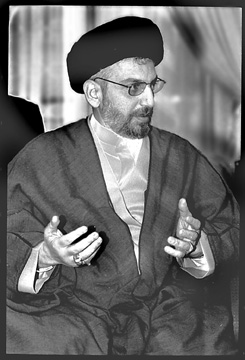

3) Fernando Suarez del Solar, whose son was killed in March, and Ghazi Al-Kabi, whose son was killed by US soldiers. The US ended up paying the family $10,000 for the killing.

4) Entering the Al-Awsiya Elementary School in Baghdad, where walls had been painted but still no promised books and supplies.

5) VFP members Michael McPhearson and Billy Kelly, at right, speak with six-year-old Ali, who has typhoid. Doctors at the Al-Qadissiyah Hospital were angry that their walls had been painted while they desperately needed basic things like antibiotics and heart monitors.

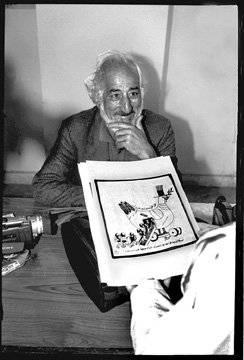

6) Cartoonist Ali-Mohammed and his vision of a US Trojan peace dove.

7) Boy with a toy gun at a black market gasoline concession, where people pay exhorbitant prices to avoid five and seven hour gasoline lines.

8) The bombed out Health Ministry, one of many wrecked buildings seen throughout downtown Baghdad.

9) Medea Benjamin, director of Global Exchange, the group that organized the trip, here speaks to Iraqi TV after a press conference for two arrested members of the Union Of The Unemployed just released by US occupation forces.

10) A regular sight seen through windshields on Baghdad streets: a US humvee on patrol with a US soldier pointing a .50 calibre machine into traffic.

11) VFP member Michael McPhearson speaks with PFC Massey from Georgia at the gate to a US base in Baghdad.

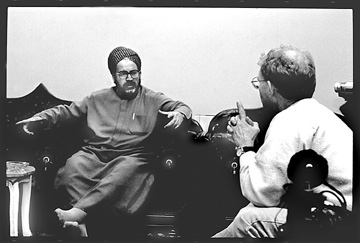

12) Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, the December presidnet of the Governing Council, a body appointed by Paul Bremer from the Coalition Provisional Authority. Al-Hakim is a Shiite leader and thinks the US occupation forces should go home.

13) VFP member Billy Kelly, right, speaks with Shiek Muayd al-Addamy, a leader at the Sunni Abu Hanifa mosque, which was attacked by US Marines during the invasion phase of the war.

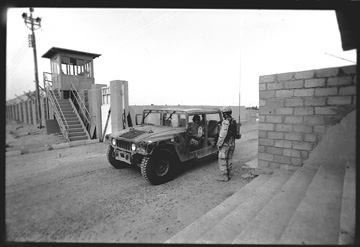

14) A base in Falluga encountered on the journey to find Mike Lopercio's son Tony.

15) Staff Sergeant Stallings from Alabama, a public affairs officer, who was instrumental in providing safe directions for Mike Lopercio to get to the base where his son Tony was stationed.

16) Mike Lopercio, left, and his son, Tony, a fuel tanker driver at Falluga who had just been promoted to Spec. Four.

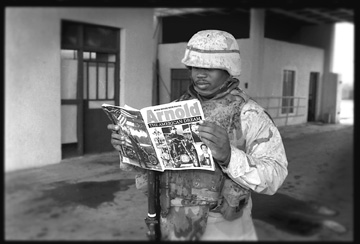

17) A soldier at the Falluga base gets up to speed on one of the more bizarre political actors back in "the world."

Photos by John Grant